Halloween Special: Close Encounters of the WTX Kind

- Jody Slaughter

- Oct 27, 2025

- 38 min read

Updated: Oct 31, 2025

Season: 2

Two of the most famous UFO cases in American history happened right here in West Texas, six years apart.

Lubbock Lights (1951): Professors watch, measure, and even photograph bluish formations.

Levelland (1957): Glowing, egg-like objects stall car engines and lift away. Seen by a dozen witnesses, including the sheriff.

A secretive Air Force unit investigates both. Its explanations raise more questions than they answer.

We follow the paper trail across the South Plains: Witness interviews, declassified files, and firsthand investigator accounts. Birds? Lightning? Black projects? Aliens?

What (or who) was cruising West Texas in the 1950s?

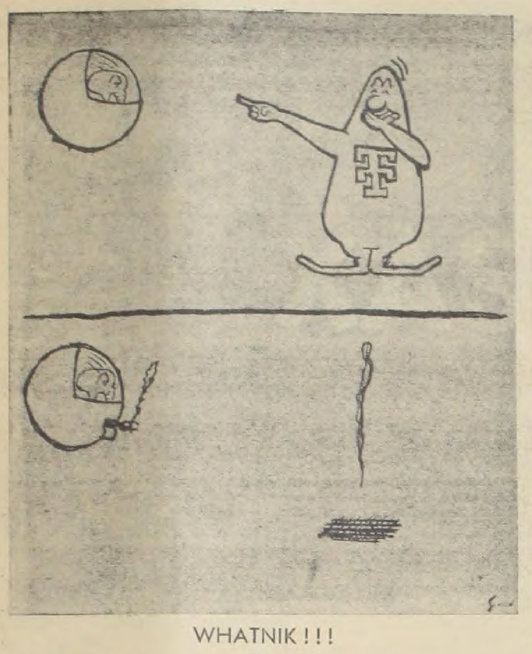

Editorial cartoon appearing in the Texas Tech Daily Toreador student newspaper, November 5, 1957

Sheriff Weir Clem national radio interview

SHOW NOTES

Cold Open: The Saturday Night Seminar (Lubbock, 1951)

Four Texas Tech scientists in a backyard, watching the sky

A semicircle of bluish-green lights races north to south

Returns on ~90-minute intervals; ~90° of sky in ~3 seconds

“Good God—what’s that?” and the pattern begins

Chapter 1: The Lubbock Lights Take Shape

Robinson, Oberg, George, Ducker time and log repeated passes

Witness calls ripple out across Lubbock and nearby towns

Always north→south; silent; faint to the eye; fast

A data-driven hunt by professors acting like…well, professors

Chapter 2: Hart’s Photos Hit the Wire

Freshman Carl Hart Jr. shoots five frames on Aug. 31

Kodak 35, 1/10s at f/3.5; the “V” shows up on film

A-J runs them, then Life Magazine picks them up

Photos brighter than eyewitness impressions—fuel for debate

Chapter 3: Ruppelt, Grudge, and the Cross-Checks

Capt. Ed Ruppelt (ATIC) flies in: interviews, reenacts, tests

Albuquerque “flying wing” with bluish lights echoes Lubbock

Matador “pear-shaped” object; a rancher’s wife sees a wing with no fuselage

Lab analysis: true point lights; panning tests; still no clean answer

Chapter 4: Theories, Tests, and an Official Shrug

Birds vs. optics vs. balloons—each explanation comes up short

IR/heat-source idea could fit “dim to eye, bright on film” (but…what flies like that?)

Professors doubt the “V”; photos don’t line up with their faint groups

Case closed on paper; “Unknown” in practice lingers over West Texas

Chapter 5: Levelland Lights the Switchboards (Nov. 2–3, 1957)

Pedro Saucedo & Joe Salaz: torpedo/rocket-like object; heat; truck dies

Newell Wright near Smyer; Robert Wixon east of town; engines/headlights fail

Sheriff Weir Clem sees a football-sized glow; highway turns bright as day

Fifteen calls in ~3 hours; a county-wide map of approach→failure→withdrawal→recovery

Chapter 6: Blue Book Changes—and Drops the Ball

Project Grudge → Project Blue Book → then the debunking era

Sgt. Norman Barth’s short swing-through; key people un-interviewed

“Ball lightning” stamped on the file despite scale/duration mismatches

Weather checks later undercut the storm narrative

Chapter 7: Beyond Levelland (Same Weekend, Same Pattern)

Amarillo couple: object blocks road; car dies; must be towed

Clovis streak; Seminole–Seagraves engine kill; multiple control-tower reports

White Sands MPs: large egg-shaped object over test bunkers (twice)

The pattern radiates across the region, not just one county

Chapter 8: What Could Do This Here?

West Texas “echoes”: Texas Tech’s pulsed-power research; Reese’s EMP testing

Tech possibilities: fields that blank radios and stall ignitions

Or not us at all—Sputnik era eyes on a nervous, glowing planet

Bottom line: Lubbock = measured witnesses + photos; Levelland = repeatable effects

Closing

If you want comfort, the Air Force will sell you lightning

If you want closure, West Texas won’t

Out here, sometimes it looks back

Enjoyed the episode?

Subscribe to WTX: A History of West Texas on your favorite app and leave a review—it helps other listeners find the show.

Further Reading

The UFO Experience: Evidence Behind Close Encounters, Project Blue Book, and the Search for Answers. J. Allen Hynek. MUFON, 1972.

The Report On Unidentified Flying Objects. Edward J. Ruppelt. Doubleday, 1956.

Credits:

Writer: Jody L. Slaughter

Producer: Jody L. Slaughter

Editor: Jody L. Slaughter

Engineer: Jody L. Slaughter

Music by:

The U.S. Airforce Band (public domain)

Additional Music Gentry Ford & the Homeless Lobos, featuring November 2, 1957 (Oh Buddy)

Contact:

Email: lubbockistATgmail.com

Twitter: @Lubbockist

Listen on:

Thanks for listening, and so long...from West Texas.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Lubbock, Texas - August 25, 1951

A handful of Texas Tech professors gather for what they call their Saturday Night Seminar—an informal backyard ritual at Dr. W. I. Robinson’s adobe home in Tech Terrace. They meet to discuss the highest intellectual pursuits. No talk of politics, religion, or women; just big questions and iced tea. Some nights they go till sunrise talking about topics like undersea canyon formations. Tonight’s topic: micrometeorites.

The core crew is Robinson, professor of geology; Dr. A. G. Oberg, chair of chemical engineering; Dr. F. E. George, retired head of physics; and William Ducker, head of petroleum engineering.

They talk meteorites and, by suggestion, watch the sky.

Around 9:20 p.m., Ducker glances up. He sees something faint. He blinks, looks again, and stands.

“Good God—what’s that?”

All four stare. A semicircle of fifteen to thirty bluish-green lights races north to south.

“It traveled very, very rapidly, and so we were all rather dumbfounded,” Ducker would say later. “Then we began to discuss it in scientific detail, and no one had had the presence of mind to make any meaningful observation except just look open-mouthed at it. We all agreed that we were remiss as scientists for having flunked our observation tests.”

Not a meteor—too dim. Aircraft? A formation? How high? Before they can frame a hypothesis, it returns. This time they’re ready: they clock it, estimate the arc: roughly 90 degrees of sky in about three seconds. Solid or transparent? With no stars visible behind it, they can’t be sure.

Ducker calls the Avalanche-Journal. Had anyone else seen it? No one had.

They don’t wait for next Saturday. Night after night, they regroup in Robinson’s yard. And around 9 p.m., the lights appear. Later they note a second pass about 10:30, then another near midnight—roughly 90-minute intervals. Over the next days they log a dozen more appearances. Always north to south. Always that fast, 90 degrees in three seconds.

They run the numbers. If the objects are a mile high, that angular speed implies about 1,800 miles per hour—more than twice the speed of sound. That should come with a sonic boom, and nothing known flies that fast in 1951. So maybe much higher—50,000 feet or more. But then you’re talking 18,000 miles per hour—orbital velocities, years before Sputnik—and spans on the order of 10,000 feet. None of that fits anything known to exist.

They do what scientists do: test. They set up outside of town. Two teams with stopwatches, elevation scopes, and two-way radios set up along the projected path outside town to triangulate altitude. They see nothing. Back in Tech Terrace, Mrs. Robinson reports the lights over the neighborhood. In town they’re visible; out in the county, they don’t show.

It might have ended there—if not for that call to the A-J.

A report from four Texas Tech professors about an unidentified flying object is certainly newsworthy. The next day the paper published an article, quoting Ducker; the AP wire service transmits the story nationwide. UFO mania has come to Lubbock.

For two weeks after publication, dozens around town—and in nearby communities as far as Lamesa—say they’ve seen the same thing. The professors interview some of them. A few don’t match what the men observed. Some do—precisely, down to time and position. Useful details are scarce; unlike the scientists, laymen are poor observers.

Except one.

On August 31, Texas Tech freshman and amateur photographer Carl Hart Jr. is in bed with the window open. He’s heard the stories; but he hasn’t seen the lights. Then he does: a V of bluish-green points appears from the north, crosses his view, and vanishes over the house. Knowing they sometimes return, he grabs his loaded Kodak 35, sets 1/10 second shutter at f stop 3.5, and heads to the yard. Sure enough, the lights make another pass. He gets two frames. Minutes later, a third pass—he gets several more.

They look faint to the eye; he isn’t sure anything will come out. Either way, at first light he takes the roll to a friend’s photo lab. The developed negatives show the lights clearly—brighter on film than they appeared to him.

He calls the newspaper. Skeptical at first, the A-J eventually runs the photos. The wire services pick them up, too. They will eventually appear in Life Magazine.

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, Ohio. Late September, 1951

Captain Edward Ruppelt is at his desk in the Air Technical Intelligence Center when the mail girl drops three envelopes onto his desk.

Ruppelt, twenty-eight, already had a war behind him—He had spent World War II as a targeting officer on bombers. Now he has a unique assignment. Since 1949 he’s been the point man on Project Grudge, the Air Force’s effort to investigate—and tamp down public anxiety over—an uptick in flying-saucer reports. In the heat of the Cold War, the fear wasn’t only what the objects were; it was what the stories could do. Moscow didn’t need a spaceship to cause trouble if a rumor could incite mass hysteria.

Two years into the job, Ruppelt had seen—and explained—just about everything. He even popularized a tidy label: Unidentified Flying Object—UFO.

He opens the first letter: a report from the 34th Air Defense at Kirtland AFB in Albuquerque.

August 25, 1951. An employee of the Atomic Energy Commission’s super-secret Sandia operation and his wife are on their back porch when a massive, totally silent aircraft glides over the house. Only seconds in view, but low enough to see: 800 to 1,000 feet, one-and-a-half times the size of a B-36, a flying-wing shape swept back like a V. Dark bands front to back. Along the trailing edge, six to eight pairs of soft, bluish lights. North to south.

Kirtland checks traffic. Nothing in the air where it should have been. A sketch is attached. The witness holds a Q-clearance—not your typical crank. Ruppelt sets it down to follow up.

Next envelope: Lubbock, Texas, same date. It’s a thicker packet—with photographs. He thumbs to the prints first. Carl Hart’s images ring a bell: the pattern of lights matches what he just read from Albuquerque.

He reads the cover report:

“On the night of August 25, 1951, about 9:20 p.m. (this was just twenty minutes after the Albuquerque sighting), four college professors from Texas Technological College at Lubbock observed a formation of soft, glowing, bluish-green lights pass over their home. Several hours later they saw a similar group, and in the next two weeks they saw at least ten more. On August 31 an amateur photographer took five photos of the lights. Also on the thirty-first two ladies saw a large ‘aluminum-colored,’ ‘pear-shaped’ object hovering near a road north of Lubbock.”

Ruppelt would write later: “This report, in itself, was a good UFO report, but the similarity to the Albuquerque sighting—both in description and timing—was truly amazing.”

He almost overlooks the third letter. This one, much shorter, is a teletype from an Air Defense Command radar site in Washington State.

Early morning August 26, just a few hours after the Lubbock sighting, two different radars paint a target at 13,000 feet, ~900 miles per hour, on a northwesterly heading, continuous for six minutes. An F-86 fighter jet is scrambled; but by the time it’s at altitude, the target is gone.

Ruppelt pulls a U.S. map from the drawer and draws a line from Lubbock to the radar station. Northwest. He checks the Lubbock times again and does the math. A sighting in Lubbock at the logged hour and a radar track in Washington a short time later implies… about 900 miles per hour.

He later wrote: “This was by far the best combination of UFO reports I’d ever read, and I’d read every one in the Air Force’s files.”

He rushes copies of the Lubbock photos to Kirtland with one instruction: show them to the Albuquerque couple without saying what they are. The wire back the next day:

“Observers immediately said that this is what they saw on the night of 25 August.”

Ruppelt books a flight. Destination: Lubbock.

Boots on the Ground

Captain Ruppelt lands in Lubbock that evening. The Reese Airforce Base intelligence officer drives him straight to meet the four professors.

“If a group had been hand-picked to observe a UFO,” Ruppelt writes, “we couldn’t have picked a more technically qualified group.”

They talk deep into the night. Ruppelt returns to Reese after midnight, he tosses and turns trying to figure out what they could have seen.

Next morning he’s at Carl Hart Jr.’s home. They stand where Hart stood and reenact the night’s events. Hart traces the path and estimates the lights crossed 120 degrees of sky in four seconds—the same angular speed the professors recorded.

With the Reese intel officer’s list in hand, Ruppelt starts knocking on other doors. Most witnesses describe the same thing: bluish lights moving north to south. Two airport tower operators say they’ve seen them, too. Not every story helps. One woman describes it as a “flying Venetian blind,” another a “double boiler.” Almost none saw anything before the professors’ account hit the paper.

In Lamesa, an eighty-year-old man and his wife report two or three bluish lights overhead—then a third pass where one of the lights made a sound: plover. The witness recognizes the sound instantly. A small, quail-sized water bird.

Ruppelt checks with the game warden. A plover’s pale belly could reflect city light, yes—but flocks of fifteen to thirty? That’s rare. Ducks, geese maybe. Plovers, not usually.

He needs to get his notes typed while they’re fresh, but he also wants the story of the pear-shaped object near Matador. He sends two investigators from Reese.

The mother and daughter say they left home about 12:30 p.m. on August 31 when they encountered a pear-shaped object, about 150 yards ahead, 120 feet in the air, drifting east. The daughter is familiar with aircraft; her husband flew in Korea. She guesses it was about the length of a B-29 fuselage. But no sound. No exhaust. A porthole was visible, but they couldn’t see anything inside . After a few seconds it shot up in a tight, spiraling climb and was gone. The investigators initially suspect that it was a balloon, but they check the weather: drifting east would have been into the wind that day.

No one has any idea how to square that.

Waiting for his flight in the Lubbock airport—connection in Dallas, then on to Dayton—Ruppelt bats the numbers around again. August 25: the flying wing was seen in Albuquerque; lights in Lubbock fifteen minutes later—~1,000 mph to make that hop. Last seen in Lubbock at 11:20 p.m.; radar in Washington just after midnight Pacific—1,300 miles in 1 hour 40—~780 mph, with the radar logging ~900. Close enough. In 1951, nothing outside of Chuck Yeager’s experimental X-1 plane flies that fast.

One thing nags him. Except for Hart’s photos, no Lubbock witness reports a V. The first backyard sighting was a semicircle; later passes were just a group of lights. Is he forcing a connection because he read the three reports back-to-back?

He boards the plane. The man in the Stetson beside him is a retired Lubbock rancher. The rancher notices Ruppelt reading an article in the paper about a meteors—there’d been a spectacular one the night before. That, of course, segues into the Lubbock Lights. Has he heard about them? Ruppelt says that he’s read a few things about it, hoping to end the conversation there, but he politely goes along. Finally, the rancher pauses, the tone of his voice shifts.

Ruppelt writes: “I’d heard this transition many times… he was going to tell about the UFO he had seen… I was wrong; what he said knocked me out of my boredom.”

The rancher tells him that the same night as the professors’ first sighting, his wife had seen something. They hadn’t told anyone in Lubbock because they didn’t want to be seen as crazy. But he would tell this stranger. His wife was outside taking sheets off the line when she came into the house as white as the sheets she was carrying. She had seen a large, silent object glide over their house: “an airplane without a body,” he says, with pairs of bluish lights along the trailing edge of the wing. Ruppelt drops his newspaper. It’s the Albuquerque description to a tee—but Albuquerque hadn’t been public. Only the two witnesses and a handful of Air Force officers knew about it.

Ruppelt presses him, but that’s all the man has. “At Dallas,” he writes, “I boarded an airliner to Dayton and he went on to Baton Rouge, never knowing what he’d added to the story of the Lubbock Lights.”

Back in Dayton, Ruppelt takes Hart’s negatives to the Photo Reconnaissance Lab.

They’ve been handled to death—scratches, dust, motion blur from panning—but the techs are able to separate artifact from image. Each point appears to be a circular, near-pinpoint light source. Comparing frames, the lights shift position in a definite pattern.

Now, for a field test: same camera, same film, same settings; Ruppelt and the lab team try to shoot a moving light at night. Hart got three photos in four seconds; the lab can manage only two, and their images show more blur. Some call it fraud.

Ruppelt canvasses professionals, including a Life Magazine photographer. A practiced hand could fire faster under excitement, they say—and a kid like Hart who’s used to shooting sports might pan smoother, yielding less blur. Still more questions than answers.

The professors, for their part, are convinced Hart is a fake. In all their watches, they never saw a V, only loose groups—and their lights were faint, near the threshold of vision. Hart’s are bright. Ruppelt asks the lab: Is there any way a light could look dim to the eye but bright on film? The answer: maybe—if the source were extremely bright in the infrared spectrum, the eye might not detect as much light as the film. What could cause that? They tell him an intense heat source might do it. Then the hedge: “But we have nothing in this world that flies that appears dim to the eye yet will show bright on film.”

Ruppelt spends weeks pulling more threads. Could anything fly that fast and stay silent? He reaches out to the National Aeronautics Lab at Langley Virginia. They tell him that not only is flight like that not possible with any known technology, there’s not even any research on how it could be done theoretically.

What about the birds? The plover idea is still the best natural fit. Lubbock had just installed bluish mercury-vapor lamps along several boulevards, including College Avenue near Robinson’s Tech Terrace home; a pale belly catching that glow could mimic a faint blue. That might also explain why the professors’ excursion outside town saw nothing while Mrs. Robinson saw the lights in town.

Ruppelt gets a city map of the new lamps. Too many reports are miles from those corridors. A tidy theory that still doesn’t fit cleanly. And one more common-sense snag: for all those passes overhead, you’d expect a honk, quack, or “plover.”

With no more leads to chase down, Ruppelt types up his official findings.

Washington: weather echo. Inside Air Force channels, the radar station’s commander vehemently disagrees—his crew knows weather on a scope, and this wasn’t it.

Carl Hart’s photos: neither proven authentic nor disproven totally.

Pear-shaped object near Matador: Unknown.Albuquerque flying wing: Unknown.The Lubbock Lights: Unknown.

Project Grudge Case File #24: Closed. Officially.

November 2, 1957 — 10:50 p.m. — Near Levelland, Texas

It’s overcast, a little mist in the air. Pedro Saucedo and his buddy Joe Salaz are rolling west on Highway 116 (now 114). Pedro—30, a Korean War vet—has been piecing together odd jobs since he got back: barber, seasonal farm hand. They’ve just turned north on a county road toward Pettit when they see it.

Off to the left, out in the distance: a flash. Lightning? It doesn’t fade. A gas flare from the oil patch? Flares don’t move. This one does—closer and closer, brighter and brighter.

As it nears the truck, the headlights flicker and go dark. The engine sputters, then dies. They coast to a stop in the middle of the road.

Pedro jumps out for a better look. Not a fireball—an object, lit in yellow, blue, and white. Torpedo-shaped, he thinks, but massive—maybe 200 feet long. More like a rocket. As it thunders overhead he feels intense heat and drops to the caliche, the pickup rocking as it passes. He calls to Joe, still in the cab, stunned.

The thing fades off toward Levelland. The truck’s headlights come back. Pedro climbs in, turns the key—the engine catches like nothing ever happened. They point the nose west toward Whiteface to find a pay phone and call the police.

November 3, 1957 — 12:05 a.m. — Near Smyer, Texas

Texas Tech freshman Newell Wright is westbound on Highway 116, headed from Lubbock to his parents’ place in Levelland, when the engine begins to sputter—cutting in and out like it’s out of gas. He has plenty. The motor dies. He coasts to a stop. The headlights fade to a glow and go out; the radio dies with them.

He steps out, pops the hood, and checks what he can. Nothing obvious. He closes the hood and looks down the highway, hoping for another car. No headlights. No help. Instead, in the road ahead, sits an oval, metallic object with a flat bottom, glowing bluish-green. It isn’t small—75 to 100 feet long, spanning both lanes.

Terrified, he dives back into the driver’s seat and works the ignition. Nothing. He looks around frantically for another car. Still nothing. He’s alone with it, he just stares, frozen between the key and the thing in the road.

After what feels like minutes it shoots straight up into the sky and disappears. He turns the key again. The engine catches. The radio and headlights come back. He eases onto the highway and drives home slowly, careful not to stress the car and risk another engine failure.

His parents are out of town on a trip and wouldn’t be home until the next day. Not sure what else to do, he goes to bed.

The Night the Board Lit Up

11:15 p.m. — Levelland Police Station

An hour earlier, Patrolman A. J. Fowler is manning the phones as night dispatcher. It’s a typical Saturday for a Texas town of eight thousand: high school kids racing the drag, a suspicious person in a downtown alley, a domestic dispute on the west side. One crank call—a drunk in Whiteface claiming a flying torpedo pulled him over. Hockley County is dry, but the bootleggers from down south keep it plenty wet. Fowler logs each call, sips coffee, and listens to the radio. A noise complaint on the north side—he dispatches a radio car. Someone flipped the picnic tables at the city park—"unit, roll through there after you break up the party.”

12:05 a.m. The phone rings again. A frantic Jim Wheeler says he was east of town on the Lubbock highway—116, about four miles out—when he came on a brilliant, egg-shaped object, roughly 200 feet long, sitting in the roadway. As he closed on it, his engine died and his lights went out. He got out to get a better look, and when he did it lifted into the sky. Around 200 feet up it disappeared, and his truck started again. Another drunk? Maybe the first guy’s buddy. Fowler hangs up and logs it.

Ten minutes later. Another call. Jose Alvarez reports a bright object circling a cotton field about ten miles north of town, near Whitharral. When he got close, his engine and headlights failed. After a short while the lights went out on the object and it disappeared; his car came back to life.

“What is going on?” Fowler mutters under his breath.

12:25 a.m. A fourth call. Frank Williams, also near Whitharral, about a mile up the road from Alvarez. On his way home to Kermit, he encountered an egg-shaped object with pulsating lights sitting in the middle of the road. As he approached, engine and headlights died. Like Wheeler’s report, it finally rises, and around 200 feet up the lights go out and his truck works again.

Now Fowler is suspicious. A string of pranks? Or something real? Either way, they have to run it down. The locations are outside the city, so he radios Highway Patrol, which sends two officers out of Littlefield. He wakes Sheriff Weir Clem, too. Clem and a deputy head out too.

1:15 a.m. Another caller: James Long, a truck driver from Waco, says he was on Oklahoma Flat Road, northwest of town, when he saw a brilliant, egg-shaped object glowing like a neon sign. Again, engine and lights failed. He stepped out; the thing shot up with a roar and streaked away.

Fowler radios the new location to the patrolmen and to Sheriff Clem.

1:30 a.m. Clem and his deputy, driving that same road, see a football-shaped light—lit like a red sunset. They estimate 50 yards wide and 350–400 feet long. It turns the highway bright as day about 300 yards ahead of their car, but their engine doesn’t falter.

The two Highway Patrolmen, several miles behind the sheriff on Oklahoma Flat, report a flash crossing the highway about a mile in front of them at roughly the same time.

By now Hockley County’s first responders are out in force. Constable Lloyd Ballen sees the object from a distance near Anton, about 15 miles northeast of Levelland—far enough away that his engine never hiccups.

Even the fire marshal, Ray Jones, catches it. 1:45 a.m. on Oklahoma Flat, he sees a streak of light to the north; his engine sputters but doesn’t die. Jones will be the last county sighting of the night.

The Aftermath

At some point in the early morning, Sheriff Clem returns to the station to take stock. In under three hours, fifteen calls have come in from around the county.

Fowler clocks out at 5:30 a.m. and goes home to try to sleep. By Sunday morning the story is everywhere. The radio station airs it. The Levelland Daily Sun and the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal send reporters to the station to talk to Clem. Press calls start hitting Fowler’s home. Around noon, he gives up on sleep and heads back to work.

Around 1:30 p.m. Newell Wright, a nineteen year old, a Texas Tech freshman, shows up to file his report. He was westbound toward Levelland on 116 just after midnight when the object stopped his car. He went home and told no one, worried about ridicule. When his parents returned from their trip—having heard radio reports on their drive back from Hobbs—they convinced him to come in. He also gives an interview to the Daily Sun.

Pedro Saucedo is called back in that afternoon for a full statement, since Fowler had brushed off his first call as a hoax. He speaks to the Avalanche-Journal.

Another stranger appears: Ronald Martin, an out-of-town trucker who overnighted at a local hotel. He says that around 12:45 a.m., driving in from the west on 116, he saw an orange ball of fire about a mile ahead. He pulled over and watched it fly over and settle in the highway about a quarter-mile away, changing color from orange to blue-green. His engine conked out and headlights died. After a few minutes it rose, turning from blue to orange again, and ascended out of sight. His truck restarted. He, too, is interviewed by the A-J before leaving town.

For Sheriff Clem, the rest are dead ends. Joe Salaz, Saucedo’s passenger, never files a statement. Jose Alvarez and Jim Wheeler, the second and third callers, are never located. Frank Williams, the fourth, presumably continued on to Kermit. Clem calls the Winkler County sheriff to get a statement; they’ve never heard of Williams but promise to check. The Winkler sheriff reportedly “turned Kermit upside down,” even issuing an appeal on local radio. Williams never turns up. The fifth caller, James Long from Waco, isn’t found either.

On Monday, November 4, the Avalanche-Journal banner reads: “Levelland ‘Flaming Thing’ Brings World Knocking on City’s Door.” Reese Air Force Base—halfway between Lubbock and Levelland—reports no aircraft in the air that night and nothing on radar.

The wires carry the story coast to coast. Front pages pair Levelland with another headline: the Soviet launch of Sputnik 2, carrying a dog into orbit—an event that, unknown to anyone in Hockley County at the time, occurred just hours before the sightings.

Levelland had its night. The calls stop. The questions don’t.

From Grudge to Blue Book

To understand the Air Force’s investigation at Levelland—and its conclusions—you have to see how drastically its UFO unit had changed since the Lubbock Lights just six years earlier.

In 1952, Air Force brass grew dissatisfied with Project Grudge. They shut it down and stood up a higher-profile, better-funded successor inside ATIC: Project Blue Book. The aim was to make a more concerted push to get to the bottom of credible sightings.

Captain Edward Ruppelt was again put in charge. He streamlined data collection with standardized forms so reports could be compared and analyzed scientifically, no matter the source.

For a time, the project thrived. Blue Book had a dedicated officer at each Air Force base worldwide to take reports in the proper format and forward them to Dayton. The project also practiced unusual transparency, issuing regular public statements on cases. When no explanation fit, they said so—and 20 to 30 percent remained officially unexplained.

But Blue Book made enemies. It was authorized to interview any Air Force witness outside the normal chain of command, which rubbed commanders the wrong way. Others inside the service argued that Blue Book’s traffic clogged intelligence channels with cranks and kooks, risking a real threat getting lost in the noise.

The pressure peaked in July 1952, in the wake of the Lubbock publicity and, more dramatically, a mass sighting over Washington, D.C.—objects seen visually and on radar over and around the nation’s most protected airspace. Headlines shouted, “SAUCERS SWARM OVER CAPITOL.”

In January 1953, the CIA convened a panel of physicists, meteorologists, astronomers, and engineers—most of them UFO skeptics who believed Blue Book was feeding a public frenzy. After about twelve hours reviewing six years of cases, the panel concluded that most already had boring, reasonable explanations; the rest, they said, would yield with just a bit more checking…but notably, that extra investigation also wasn’t worth the effort. They recommended that the Air Force de-emphasize UFOs and mount a debunking campaign, even enlisting mass media—Walt Disney, celebrities, and other high-profile voices—to ridicule the subject and discourage new reports. They also urged domestic intelligence and law enforcement to monitor independent civilian UFO groups and discredit them as potentially subversive.

Those recommendations landed on Ruppelt’s unit like a 200-foot UFO. Transparency was over. From then on, Air Force personnel were allowed to comment publicly only on cases officially “solved.” Unexplained cases were classified.

A new field unit took shape as well, the 1066th Air Intelligence Service Squadron (AISS), based far away from Ruppelt and Blue Book at Colorado Springs. The AISS was tasked to handle the most sensitive UFO reports with potential intelligence or national-security implications, that left Ruppelt’s outfit just the trivial reports. His staff was cut as well—from ten down to three. Ruppelt could see the writing on the well and requested reassignment in August 1953. The era of intensive, open UFO investigation inside the Air Force had effectively ended.

By 1957, Captain George T. Gregory ran Blue Book. A staunch UFO skeptic, Gregory’s office did little in the way of scientific fieldwork on reports escalated from the new intelligence unit. His mission was to reduce the tally of “unknowns,” full stop. If a witness mentioned a “balloon-like” object, Blue Book labeled it a balloon and marked the case solved with minimal follow-up. The unsolved case file shrunk from 20-30% to 2-3% overnight.

So where the Lubbock Lights had been investigated by Ruppelt himself who spent days on the ground chasing leads, interviewing witnesses across the area, staging reenactments, and soliciting expert opinions from top government labs—the Levelland investigation would look nothing like that at all.

Sgt. Barth comes to town

Unbeknownst to law enforcement as they chased glowing eggs around Hockley County, they had an eavesdropper that night: the U.S. Air Force. The Provost Marshal’s Office at Reese Air Force Base (what today would be the Security Forces Squadron) had been monitoring police radio traffic from the start.

Around 11:00 p.m. on November 2, Provost Marshal Major Daniel Kester received a report that an airplane had crashed and was burning near Levelland. By riding the law-enforcement airwaves, Reese quickly learned it wasn’t a crash at all but a series of UFO reports. On Sunday morning, November 3, Kester and a counterintelligence officer drove to Levelland to learn what the police had, and what they knew about the witnesses. They also visited one or more of the reported sighting locations. Per protocol, they relayed everything to the 1066th Air Intelligence Service Squadron (AISS) in Colorado.

On Monday, November 4, Staff Sergeant Norman Barth from the AISS arrived at Reese. It bears noting: where the Lubbock Lights had drawn Captain Ruppelt himself, Levelland drew a staff sergeant—roughly seven pay grades lower. Nothing against NCOs, but it’s a meaningful contrast.

Whatever Barth did that Monday isn’t recorded—presumably he was briefed by Major Kester. But on Tuesday around lunchtime, he appeared at the sheriff’s office in Levelland and interviewed Sheriff Weir Clem, Pedro Saucedo, and Newell Wright. Their accounts generally matched what had been reported to Patrolman Fowler and to the newspapers.

As noted earlier, Saucedo was the only one of the original callers who could be located the next day. Then Newell Wright—who hadn’t called at all—came in. Finally Ronald Martin appeared with a similar story. After giving a statement to Clem and the Avalanche-Journal—and even posing for a photo—Martin could never be located by Barth, despite supposedly living in Levelland. Barth’s report was openly snide: Martin was “a prime source who apparently gave his story to the press rather than phone us—as is often the case of people not wanting us to check their story.”

Barth only spent about three hours in Levelland, a fact that Sheriff Clem would pointedly note later. No interview with Fowler, who took all the calls, even appears in his report. According to Clem, Barth just said, “Well, I’m gone,” and left. None of the witnesses heard from him again.

After the Levelland stop, Barth drove to Littlefield to interview Lee Ray Hargrove, one of the Highway Patrolmen who had seen the object as in the distance.

There was also a witness the sheriff never knew about: Technical Sgt. Harold D. Wright of Reese. He reported that at 11:35 p.m. on Nov. 2, about two miles south of Shallowater (roughly twenty miles northeast of Levelland), he and his wife saw a three-second white/orange flash in the direction of Levelland. Their headlights and radio cut out for the same three seconds—but the engine didn’t. Assuming it was ordinary lightning, they drove on. He reported it to Air Force security the next day after hearing radio coverage; Barth took his statement as well.

Finally, Barth interviewed J. B. Cogburn of Whiteface, who saw an object two days after the main wave. Cogburn described something “about the size of a basketball at arm’s length,” attached by a hose or cable to a stationary object on the ground—almost certainly a weather balloon. No engine failure, no electrical effects. Something any reasonable person would chalk up as unrelated.

Those were all the witness interviews Barth conducted before returning to Colorado.

On November 18, the formal AISS report was filed—authored not by Barth but by his commander, Lt. Col. William Brunson, who had not visited Levelland and had not interviewed anyone himself.

His conclusions:

Pedro Saucedo was unreliable; his report was a figment of his imagination.

Sheriff Clem, Patrolman Hargrove, and TSgt. Wright had seen only a light/flash, attributed to ordinary lightning.

Cogburn’s sighting was rightly dismissed as a balloon.

Only Newell Wright’s case gave him pause. Brunson floated four possibilities: St. Elmo’s fire or similar, ball lightning (more on that shortly), reflections on low clouds from oil-field gas flares in the area, or some combination of the above.

Brunson forwarded Wright’s case to Captain George T. Gregory and Project Blue Book as “unsolved.”

Ball Lightning

Now, before we continue, let’s kind of re-establish the flow of information through the funnel, because I realize it is a lot.

Fifteen calls hit the Levelland switchboard over the night and early morning of November 2 and 3. Of those, nine callers gave names and descriptive statements that Patrolman Fowler logged.The Next day, Two additional witnesses—Newell Wright and Ronald Martin—came forward.One additional witness, Harold D. Wright (no relation to Newell), reported his sighting only to the Air Force.

That yields 16 witnesses and 12 unique sightings reported in some form. Of those 12, seven included vehicle failures.

By the following day, 12 of the 16 witnesses were reachable. Ronald Martin then went silent, leaving seven sightings and 11 witnesses available to Sergeant Barth. He only interviewed five.

Despite over half of the original sightings involving vehicle failure, Barth spoke to only two of those—Saucedo and Newell Wright. Saucedo’s report was then discounted outright, which left the Air Force treating the vehicle-failure pattern as a single case: Newell Wright’s. The remaining reports that mentioned only a light in the sky were easily filed under lightning.

As mentioned previously, the only thing Captain George T. Gregory, the new head of Blue Book, hated more than UFO cases were unsolved UFO cases. When Col. Brunson’s report reached his desk on November 18, “unsolved” wasn’t going to stand. Gregory quickly latched onto two words in the AISS report, ball lightning.

Now, ball lightning is a very poorly understood phenomenon, even more so in 1957 when many scientists doubted it existed at all. In essence, it’s a glowing, spherical electrical phenomenon sometimes reported during thunderstorms—extremely rare, fleeting, typically seconds long, and small (a few feet across at the largest). Reports outside thunderstorms were rarer still and usually tied to an electrical trigger like a short in electrical wiring. Some anecdotes linked luminous effects to earthquakes, but even those were brief and small. By contrast, Levelland accounts spoke of 100–200-foot objects, color shifts, repeated back-and-forth travel over miles, and—most critically—engine and headlight failures. None of that matched any established literature on ball lightning – then or now.

It’s not obvious either where the ball-lightning idea first entered the file. It may have come from a press quote—an Arizona meteor museum curator floated it in early coverage—not exactly a specialist in obscure atmospheric electricity.

Sergeant Barth did speak with Dr. Ralph Underwood of Texas Tech, whose remarks Blue Book later quoted. Barth was obviously asking very leading questions:• Could conditions have supported St. Elmo’s fire or similar? Underwood said possibly.• Could gas flares reflect off a 400-foot cloud base? He said they could.Notably, St. Elmo’s fire is a different phenomenon than ball lightning—a coronal glow on pointed, elevated conductors (masts, spires, wing tips) during electrical storms. It requires an “antenna,” not a bare roadway.

And while Hockley County does have oil and gas activity, the wells and gas plants are west of Levelland—not east toward Lubbock, where Newell Wright stopped.

Dr. Underwood ultimately said the two possibilities he saw were either a natural phenomenon not fully understood or that the objects came from outer space—which he said he did not personally believe. He did not actually name ball lightning.

By early December, media pressure on Blue Book was intense. A TV crew was due in Dayton on December 5 for a three-hour documentary, with Levelland as a marquee segment. Gregory needed to give them something solid. The last thing he wanted was the word unsolved anywhere around the Levelland case.

So he circulated a memo to Blue Book’s Air Force and civilian scientific advisers asking them to either endorse the ball lightning hypothesis or state their objections. In his accompanying summary of the case, he hit only the elements that fit ball lightning; it left out the awkward parts—size, road-center “landings,” the vertical “shoot-ups.”

He asked two primary questions:

If ball lightning could not explain all aspects, could ordinary lightning? What effects would normal lightning have on nearby electrical circuits?

And could oil vapor suspended in mist be ignited into a brilliant ball of light like the witnesses described?

The replies soon came in:

Advisor #1 (name redacted) said a combination of normal lightning and moisture could explain the reports. He explicitly wrote that, “in spite of occasional references to ball lightning in supposedly respectable publications, [ball lightning] is not sufficiently respectable scientifically to be used to explain any of these sightings.” On Gregory’s specific questions: No, lightning would not affect car engines inside a closed hood (it essentially serves as a Faraday cage), and that it was exceedingly unlikely that oil vapor in air would ignite into a globe.

J. Allen Hynek, an astrophysisist with the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Air Force’s long-time astronomical consultant, noted that “conditions were propitious for St. Elmo’s fire or a ball-lightning-type electrical discharge and we have the proper stage setting for the sightings reported.”

Advisor #3 (name also redacted—tellingly, the only fully credited document would be the one agreeing with ball lightning) wrote, “there is just enough truth in this hypothesis (the existence of charged clouds and ball lightning to make it appear as a reasonable explanation.” Hardly a ringing endorsement. He added that if ionization were burning oxygen in a sizeable volume, you’d expect an inflow and noticeable wind—something not seen in witness accounts.

But none of the replies had unequivocally rejected Gregory’s preferred answer, ball lightning, so he wrote his final report. On January 3, 1958, Blue Book released its conclusions:

The phenomenon was undoubtedly related to the meteorological conditions at the time—fog, rain, mist, low clouds, and lightning—which he said was “definitely established.”

“Probably contributing” were oil fires then burning in the area.

All of the above were conducive to a ball-lightning manifestation.

Ball lightning matched the reports because:a) it can take spherical or elliptical shapes;b) it is predominantly blue or blue-white;c) it can float some distance above the ground; andd) nearby discharges can ionize the air and affect moisture-laden ignition components of a motor vehicle.

Project Blue Book file 23D 24-0-246 was closed. Officially.

The response

Levelland should have been happy, right? They hadn’t been visited by aliens. They had been witnesses to a rare atmospheric event during a lightning storm—something few in the world had ever seen. How lucky.

But they weren’t satisfied at all. Especially Sheriff Weir Clem, who thought the weather explanation was preposterous. He reported clear skies with only some “thin, wispy clouds” when he saw the object, and he pointed out that the moon was fully visible.

Troy Morris, a reporter with the Levelland Daily Sun who was out late that night chasing the reports, didn’t encounter any mysterious object—but he did note that the sky was “clear or nearly clear.”

Blue Book’s ball lightning explanation hinged entirely on strong electrical storms in the area. But was there lightning at all?

For an incident that generated international headlines and a government investigation, nailing down the weather that night is surprisingly hard.

According to the Air Force report, the Lubbock weather station—32 miles east of Levelland—showed overcast and drizzle/light rain. The only witnesses in the Air Force interviews who mentioned weather were Newell and Harold Wright, who reported light rain and “mist,” respectively. That tracks: both were east of Levelland toward Lubbock.

The climatological data for Levelland itself showed less than a quarter inch of rain on November 2, and only a trace on November 3—implying any rain had ended or was ending by the time the sightings began.

Lubbock reported thunderstorms the morning of November 3, hours after the last Levelland sightings, while Levelland reported no thunderstorms at all.

In 1967, atmospheric scientist Dr. James E. McDonald at the University of Arizona revisited the Levelland case to test the weather–phenomena angle. He interviewed the editor of the Levelland Daily Sun, who told him emphatically that the early hours of November 3 were “clear or nearly clear.” McDonald concluded that a cold front had passed earlier on November 2; conditions were not present for lightning; very little rain fell; and there were no storms at the time of the sightings.

So how did Project Blue Book land somewhere else—claiming “severe electrical storms in Levelland on November 2–3”?

As noted earlier, Captain Gregory wrote in Blue Book’s final that “lightning discharges were definitely established” by “numerous investigative reports.” But the reports he leaned on were Clem’s, Patrolman Hargrove’s, and Sgt. Harold Wright’s descriptions of a light/flash. But it was Col. Brunson at AISS, not the witnesses, who had dismissed these reports as lightning in his report. Now the Air Force was using that to justify the lightning hypothesis. It was circular logic.

Blue Book’s conclusion also downsized the objects to baseball–basketball scale, never mentioning the 100+ foot lengths reported by most witnesses. Only Newell Wright used “baseball,” in his description and he specifically said “the size of a baseball at arm’s length,” which only helps if you know the distance to the object. (The sun and moon are “fingernail-sized” at arm’s length.) The lone basketball mention came from J. B. Cogburn, who saw an unrelated weather balloon two days later.

J. Allen Hynek the civilian Blue Book advisor at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory had signed off on Gregory’s ball-lightning conclusion at the time. But he later had misgivings. In his 1972 book The UFO Experience, Hynek wrote that when Gregory’s urgent request reached him, he was working around the clock for the Air Force tracking Sputnik 2. Without time to properly evaluate the claims, he “hastily concurred” with Gregory’s ball-lightning evaluation on the assumption that an electrical storm was in progress. Years later, after reviewing the initial witness reports, he acknowledged there was no electrical storm in Levelland at the time—and added, “had I given it any thought whatever, I would have soon recognized the absence of any evidence that ball lightning can stop cars and put out headlights.”

Dr. McDonald, in his 1966–67 review, reached the same verdict. He systematically dismantled the ball-lightning hypothesis: the weather setup—a large high-pressure air system over the area—was “completely antithetical” to convective activity and lightning; the sizes reported (100–200 feet) were far beyond known ball lightning; there was no evidence ball lightning could stall engines and kill headlights. He also pointed out that the “wet ignition” idea conflicted with the fact that the engines restarted immediately when the object departed. That made no sense, and was “entirely inconsistent with the wet ignition idea,” he said.

McDonald did not definitively label Levelland extraterrestrial, but he argued the evidence pointed to a technological cause, not a natural one—the objects behaved as if under intelligent control. He left the status “unknown,” and wrote that, absent any evidence of domestic or foreign technology capable of what was reported, an extraterrestrial explanation was “the least unsatisfactory” conclusion. That’s a very academic way of saying space aliens were the “most likely” explanation.

Just for argument’s sake, let’s grant that lightning storms were in the area and test Blue Book’s premise. I asked my AI assistant to stack the odds:

probability that any given storm produces ball lightning;

probability that it’s in the 99th percentile for size and for duration;

probability that such an extreme event occurs seven times in different places across ~250 square miles in a three-hour window.

The output filled the screen with zeroes—on the order of 1 in 10⁷⁰. That’s the kind of number with no practical name. For context, it’s like one person winning every lottery on earth, every day, for the next 100 million years. It’s an AI back-of-the-envelope, so take it with a grain of salt—but it makes the point: the odds that ball lightning explains Levelland are essentially zero.

So what was it? A few possibilities—none very satisfying.If it was natural, it was something never observed before or since.If it was technological, where did the technology come from? Either extraterrestrial—which isn’t something we can’t prove here—or man-made. If it was man-made, who made it?

Now, I owe you an apology, because I’ve held back one crucial piece of information so far. Would it surprise you to know, that Hockley County wasn’t the only place these same objects were seen that week?

Beyond Levelland

Amarillo, Texas — Saturday, Nov. 2, 1957, 8:00 p.m.100 miles north of Levelland. Three hours before Pedro and Joe’s sighting. A young couple returning from Palo Duro Canyon in fog encountered an object blocking the road. Their engine died; the object flew off. Unlike the Levelland cases, the car did not restart and had to be towed into town by a passing motorist. Back in Amarillo they told a patrolman, who laughed and didn’t even take their names. He finally reported it the next day, after the Levelland news broke.Around the same time, two control-tower operators at the Amarillo airport reported a “blue gaseous object” moving swiftly and leaving an amber trail.

Clovis, New Mexico — Saturday, Nov. 2, 1957, 8:00 p.m.Seventy miles northwest of Levelland. Two hours before Pedro and Joe. Radio-station owner Odis Echols and his family saw a “streak of light like a fireball” moving southeast.

Seminole–Seagraves, Texas — Saturday, Nov. 2, 1957, 8:30 p.m.50 miles south of Levelland. An hour and a half before Pedro and Joe. A motorist driving between Seminole and Seagraves reported a bright light hovering over the road that killed the engine and headlights. No other details were taken.

White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico — Sunday, Nov. 3, 1957, 2:30 a.m.230 miles west of Levelland. Two hours after Sheriff Clem’s sighting. Military police Cpl. Glenn Toy and PFC James Wilbanks were on jeep patrol near the Trinity test site when they saw a very bright, egg-shaped object, 75–100 yards in diameter. It descended and stopped about 50 feet above the A-bomb observation bunkers. The light went out; they watched the darkened object for about ten minutes, then rushed to Stallion Site HQ to report it. A subsequent search found nothing.

White Sands Missile Range — Sunday, Nov. 3, 8:00 p.m.Eighteen hours later. Another jeep patrol—Spc. Forest Oakes and Spc. Henry Barlow—at the same bunkers reported a similar object: a large bright light, bright as the sun, hovering 50 feet above a bunker. It took off, began blinking on and off, and disappeared.

Orogrande, New Mexico — Monday, Nov. 4, 1957, 1:10 p.m.45 miles south of White Sands—seventeen hours later. James Stokes, a 20-year Navy veteran working at the Holloman Missile Development Center, was driving back from El Paso when he saw an egg-shaped object, “like a pistol target with rings.” As it passed overhead he felt intense radiation-like heat—“like a giant sun lamp”—and his new Mercury’s engine stopped. He said ten other vehicles were stopped along the road too. The Air Force said it couldn’t locate other witnesses, but an Alamogordo radio station interviewed Bryan Lindsey, a journalist and former Alamogordo newspaper reporter, who said his family saw the same object.

Wichita Falls, Texas — Monday, Nov. 4, 1957, 9:00 p.m.About 220 miles east of Levelland—seven hours later. James Phillips was listening to the radio when all the lights in his house went out and the radio began to buzz. Outside, he saw an object with a grayish-blue blinking light pass overhead. His lights returned quickly, but the radio hiss continued until the object was gone several minutes later.

Alamogordo, New Mexico — Tuesday, Nov. 5, 1957, 4:30 a.m.Twenty miles east of White Sands—eight and a half hours later. Don Clark, a civilian radar technician at Holloman AFB, reported a stationary, cigar-shaped object with an orange glow, hovering ~15° above the horizon over the San Andres Mountains west of town. He went inside to get his camera; when he returned, the object had vanished.

Project Blue Book, of course, had simple explanations for these subsequent sightings:

The first White Sands jeep-patrol object was just the moon peeking through broken clouds.

The second was Venus.

The James Stokes sighting at Orogrande: a hoax inspired by Levelland—an odd charge for someone working in sensitive missile programs.

None of the rest appear to even have been investigated

A UFO legacy

Here’s where we leave it. At least for now.

Lubbock and Levelland sit like two bookends on a dusty West Texas shelf. Same sky, different riddles. In Lubbock, 1951, we get those cool, surgical flights of bluish points—scholarly men with stopwatches, heads craned back, trying to measure the unmeasurable. In Levelland, six years later, it’s the sky that’s falling that fails. Glowing eggs in the road. Engines die. Headlights go dark. Radios turn to vipers, hissing into the night.

The Air Force gave Lubbock a shrug and Levelland a lightning lecture. The people who were there didn’t buy either. People like Sheriff Clem who looked up into a clear sky and then got told it was storming.

But we’ve got 70 years of knowledge that they didn’t have.

Lay the sightings over the sensitive real estate of the Southwest. Look where the compass points. Holloman, Kirtland, Cannon, and Reese Air Force Bases. White Sands and Trinity. Los Alamos. If you wanted to test something you could neither explain nor publish, that corridor between West Texas and Eastern New Mexico would be a tempting classroom. With Roswell lying right in the center. And the desert can keep a secret too. Like July 16th, 1945, when the sand turned to glass and the west lit up like the sun.

If this was a black project, if you were building a craft that played with very strong electric or magnetic fields—something that ionizes the air, throws off a plasma skin, and bathes the dark countryside in invisible energy—what would break first? Old-school 1950s cars run on points, coils, condensers, and long unshielded leads just waiting to be bullied by a strong enough pulse. The modern military has since proven it can stall engines with targeted, directed energy. High-power microwave systems are built to do exactly that. Back then, we didn’t have the vocabulary. The phenomenon would have seemed… supernatural.

What about EMP—the Electromagnetic Pulse? We learned in 1962 that a single, powerful detonation above the Pacific, Starfish Prime, could reach across thousands of miles and knock out streetlights in Hawaii. The physics is boringly elegant: a fast electromagnetic wave making mischief.

What’s truly fascinating? West Texas didn’t just shrug and go back to cotton and cattle. Within a decade of Levelland, Texas Tech stood up a research effort in plasmas and pulsed power that’s still growing today. Think controlled lightning in a box – a quick blast that can rattle wires and coils.

And Reese? The old Air Force Base that listened in on Levelland’s crazy night is no longer a sleepy abandoned runway. It’s now the Reese National Security Complex, working on EMP testing and other pulsed-power work. Different century. Same, charged dirt. That is not proof of anything about 1957. But it is an echo. A very loud echo.

What about a new kind of propulsion? There are theories—half-finished or gathering dust (as far as we know)—that all rhyme with the same thing: make your own weather around a craft. Think super-fast air that blanks radios, or charged air that makes sparks refuse to jump. If something carried its own bubble of electricity with it, your whole world would glitch long before you knew what you were seeing.

Or maybe, just maybe, it wasn’t us at all. The fall of 1957 was loud in the Heavens. Sputnik 1 was already beeping overhead; Sputnik 2 went up the very weekend Levelland lit the phones. If you weren’t from here—if you were just… passing through—and you wanted to check in on the loud primates who’d learned to throw rocks into the sky, where might you visit? At the rings of radar around Washington? At the desert that once bloomed with radioactive fire? At places where we keep secrets and pretend we don’t. Or maybe you’d pause above a county road and simple watch the humans stop in their tracks.

Here’s what’s left when the dust settles. Lubbock gives us photos and a cadre of witnesses who timed and triangulated what they saw like professionals, instead of the country bumpkins that cliches allow.

Levelland gives us a repeating pattern: approach… failure; withdrawal… recovery. Not a flash in a thunderhead. A cause and effect. Intelligent intent. You can dismiss one witness. Two. Maybe three. But when the pattern draws its own map crisscrossing county roads, the burden quietly shifts. From “prove it happened” to “prove it didn’t.”

If you want comfort, the Air Force will sell you lightning. If you want closure, West Texas won’t.

So here’s my Halloween benediction: the next time you’re out late on 114 and the sky is low and featureless, kill the radio. Roll the window down. Listen to your engine breathe. If the sky lights up with something you can’t quite explain, remember those nights. Remember Lubbock. Remember Levelland. Remember that between the mercury lamps and the missile ranges there’s a long list of questions, and that not knowing is sometimes the honest answer.

Whatever it was, we looked at it, and it looked back. And every so often, out here, it still does.

Closing

Thanks for listening to the West Texas Podcast, I’ve been Jody Slaughter. I know I say this every time, but if you’ve never ventured over to wtxpodcast.com, this is the episode to do it. I’ve got a trove of maps, photos, declassified documents, and much more over there. Check it out.

As always, music has been performed by my AI band, Gentry Ford and the Homeless Lobos. Check them out wherever you stream music. Additional music this week has been from the Air Force Band out of Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton Ohio, the headquarters of Project Blue Book, available in the public domain.

That’s all for now, but check back soon for a brand new episode. Be sure to subscribe to the show on whatever platform you listen on so you’ll never miss one. Here’s to hoping your photos are properly exposed, your engines are running, and you never stop looking up at the sky. For now, so long…from West Texas.

Comments